A selection of short reflections written ahead of Christmas 2024 by members of the Theos team. 12/12/2024

Let Your Choices Reflect Your Hopes

By Andrew Graystone

God, who said, “Let light shine out of darkness,” made his light shine in our hearts to give us the light of the knowledge of God’s glory displayed in the face of Christ.” – 2 Corinthians 4:6

It’s said that human beings can survive about five weeks without food, and about five days without water, but we can’t survive five minutes without hope.

Of course, hope comes in different shapes and sizes.

I hope the sun shines for the wedding on Saturday.

I hope Stockport County will beat Exeter at the weekend.

Then there’s the altogether more serious stuff.

I hope I can make my money stretch to the end of the month.

I hope she makes it through the night.

I hope it works out this time.

Is hope any more than optimism – a glass–half–full personality trait that comes naturally to some but not to others? I think it is. Christian believers are amongst those who choose hope, even when cynicism might be a lot easier. We can also cultivate hope, practice it, and make it a habit of character. Without being Panglossian, we can decide to orient ourselves towards a future that is good.

On the basis of that choice we can live into the best possible future, not the worst one. In his autobiography, Nelson Mandela urged people to ‘Let your choices reflect your hopes, not your fears’.

The season of Advent calls us to be realistic about the present darkness. But it also gives us glimpse into God’s future. It is precisely because of the darkness of this time of year, and the darkness of our world, that the rows of lights strung up on the houses all down my street seem so defiantly hopeful.

It is a matter of choice to believe that the light at the end of the tunnel is getting nearer, not further away. Illuminated by that tiny light, we are called to the work of liberation in the mess and the muddle of our present world. We work to set free people who are oppressed and dress the wounds of people who are hurting. We seek to bring hope to people who don’t have much of their own. It’s our choice to enjoy God today, and to live in the light of the freedom that we believe is coming tomorrow.

A Whisper in the Turmoil

By George Lapshynov

In the five days before Christmas, one of the vesper hymns of the Orthodox Church proclaims: “The prophecies of all the prophets have been fulfilled, for Christ is born in the city of Bethlehem of the pure daughter of God”.

The miracle of God’s incarnation marks the culmination of centuries of anticipation. But for those in Judaea at that historic moment, it was a time of profound uncertainty – politically volatile, economically precarious and spiritually fractured. The Roman occupation was enforced by a tyrannical king, while within Judaism, ideological and theological divisions ran deep.

Yet amid the crises, God’s plan of redemption was quietly unfolding. As Judaea teetered on the brink of collapse, Christ was born, as St Paul would later write, “like a thief in the night” (1 Thess. 5:2).

As the star rose over Bethlehem and the Magi set out on their journey, many were lamenting the ruinous state of their world. As the archangel Gabriel delivered his message to the Virgin Mary and the Holy Spirit descended upon her who was to become the ark of the New Covenant, Herod was plotting another vanity project. And while the Saviour was being born, most people, absorbed in the mundane activities of life, carried on, oblivious to the divine mystery unfolding in their midst.

Christians like to imagine that the whole world stood still in wonder that night, captivated by the angelic chorus. In truth, it stood still only for those who had “ears to hear” (Matt. 11:15). For the rest, life went on as usual.

Two thousand years later, we live in an age marked by its own turbulence – rife with cost–of–living crisis, looming global war, and assisted suicide debate. And while our own leaders are no Herods, it very much seems that we will never get a break from history’s cycles of turmoil.

Thankfully, Christmas reminds us that our hope is not in the fleeting promises of political leaders, nor should we look to them for our salvation (Ps. 146:3). The time to pause is now. God, who works unceasingly in the world, is about to become man so that we may become God. So let us be very still: we might just catch a whisper of the distant hymns of the angelic choir and taste the faint perfume of myrrh and frankincense in the air as the Magi draw near to worship the divine made flesh.

No Strings Attached

By Rosie Bromiley

Only last week our television plunged onto the floor, the screen irrevocably scarred with black static. But thanks to a friend’s kindness, we were offered their unused spare. Dad came home cradling the new screen, wrapped in the ‘swaddling cloths’ of old towels and bubble wrap. He echoed how our friend had threateningly commanded, “Don’t even think of giving me anything for it! No chocolates, no wine, nothing!”

The parallels are obvious here (though the 24–inch display Toshiba isn’t exactly the Son of God)! But giving to each other at Christmas is where we showcase our feeble yet radical imitations of God’s love.

Gifts have received bad press this year. Cabinet ministers were criticised for accepting ‘freebies’ from donors including clothing, glasses, and Taylor Swift concert tickets. The implicit source of the outcry: what do these donors get in return? The implications of such a question seemingly reek of corruption.

Sociologist Marcel Mauss identified human patterns of giving in his 1925 essay The Gift. In short, if I give you something, there is an unspoken obligation for you to return the favour. Of course, this is not just about physical presents. We give our time, our service, our attention. Principles of reciprocity become relational, binding our communities together but not always for good.

For years, money expert Martin Lewis has been all too aware of the dangers of reciprocity. In The Martin Lewis Money Show Live from 2023, he advised against excessive giving, encouraging viewers to make ‘Christmas pre–NUPs’ (No Unnecessary Presents) saying, “Sometimes the best gift is releasing others from the obligation of having to give to you.”

How heartbreakingly easy it is to taint what should be kindness. Our cherished connections to each other are susceptible to be stained either by ulterior motives and selfish expectation of reward, or we are crushed by the duty to reciprocate.

It’s why the incorruptible gift of the Word made flesh is so powerful. Jesus was given to humanity out of the relentless, free–flowing stream of love that pours from the Father to save us from death (John 3:16). He did so without expectation of repayment. No matter how hard we try, we always fall short of fully returning the favour. Christmas is a precious opportunity to defy these patterns of obligation. Instead, we can give with untethered generosity and receive in humility as we mimic an otherworldly love.

What Hides Behind Christmas?

By Madeleine Pennington

Christmas might be the most wonderful time of year, but it can also be a stressful carnival. Your favourite present–to–be is currently someone else’s panic that you haven’t been ‘crossed off the list’ yet. What began as a careful budget is perhaps already a strained overdraft. Every roast turkey represents a farmer’s busiest time of the year. And so many of these burdens are hidden – whether in a lunch break, before sunrise, or before the King’s Speech.

Much of the work of the first Christmas is also hidden to us now. Some of it has simply been lost to time. I wonder how much of Mary’s pregnancy was over–shadowed by pelvic girdle pain; how Joseph planned for the lost income that would no doubt result from a long trip to Bethlehem; who cleaned up the stable after Jesus arrived.

Deeper still, though, another kind of work was happening – not made by human hands. The Bible talks of all babies in the womb being “taught… wisdom in that secret place”. Did even Mary fully grasp what extraordinary Wisdom was growing within her? Or did she sometimes doubt the truth of that strange encounter with an angel, many months previously before her belly had started to grow? Was she, in fact, the one being taught in secret? And who else? How were Joseph, the innkeeper, the shepherds, the wise men, all being prepared – no doubt, without knowing it – to encounter the “firstborn of all creation”?

Christmas is the celebration of something unexpected bursting into sight and touch – the Word becoming flesh – and with it, the recognition that a living God continues to break unexpectedly into our own time and place. But before that, there is preparation. Where, then, might the hidden work of God be in our own lives this year? For, in the words of Rowan Williams,

He will come, will come,

will come like crying in the night,

like blood, like breaking,

as the earth writhes to toss him free.

He will come like child.

Interested in this? Share it on social media. Join our monthly e–newsletter to keep up to date with our latest research and events. And check out our Supporter Programme to find out how you can help our work.

]]>

Nick Spencer speaks with Harvey Whitehouse, Chair of Social Anthropology at the University of Oxford. 10/12/2024

The claim that evolution can help us understand, even explain, the modern world and modern mind has not always had a happy history, veering between overclaim and catastrophe. But the opposite idea – that everything is culture and nothing nature – is hardly more convincing.

So, can we threat this needle? Can we have nuanced and realistic understanding of the impact of evolution on us today without going down the rabbit hole of determinism.

So, what impact has evolution had on us – our communities and societies, our morality and our religion.

Purchase Harvey’s book here.

Interested in this? Share it on social media. Join our monthly e–newsletter to keep up to date with our latest research and events. And check out our Supporter Programme to find out how you can help our work.

]]>

Nick Spencer speaks with Historian Jonathan Clark. 03/12/2024

The Enlightenment has become weaponised over recent years. Numerous public figures, not all of them historians, have lined up to state defiantly that it needs protecting from… postmodernity? populism? religion?… take your pick.

But what is – or was – The Enlightenment? What are we being called to defend here? Is The Enlightenment actually a thing? Was it even “a thing” in the first place? And if not, when did we start talking about it, and why?

Purchase a copy of Jonathan’s book here.

Interested in this? Share it on social media. Join our monthly e–newsletter to keep up to date with our latest research and events. And check out our Supporter Programme to find out how you can help our work.

]]>

Hannah Rich introduces her report exploring the response of local churches to the riots of summer 2024. How can our country and communities heal? 02/11/2024

It is now almost four months, or 120 days, since the most extensive outbreak of riots for a decade swept across England, sparked by the murder of three young girls in Southport. Put another way, that’s 120 daily news cycles that we have moved through since then, the pace of which makes the fractious heat of late July and early August seem like a dim memory on a snowy day in November.

Our new report Disunited Kingdom? explores the response and contribution of local churches in areas affected by the riots, both immediately and over the longer term in rebuilding communities. In September 2024, we interviewed 16 church leaders in 11 different places across England where there was significant rioting, including locations where hotels and mosques were attacked.

We found that churches were well–placed to respond in several ways. Firstly, they were able to leverage their strong community networks to work with other faith and activism groups locally. Through these, church leaders were often pre–emptively aware of the coming riots and thus able to offer solidarity and support to mosques and other local targets of violence.

Secondly, they drew on their institutional relationships with local police and local government. Coupled with their connection to other faith groups, this meant churches were well positioned to share reliable information with their communities and vice versa.

Thirdly, they maintained a trusted presence in the community, even when this was challenged or threatened by the riots themselves. Where the church could not fulfil its intuitive response of being a place of safety when the buildings were literally at the centre of the violence, communities still found ways of supporting vulnerable congregation members and making their presence felt.

Lastly, churches used their convening power to draw the community together for vigils, prayer events and moments of much–needed reflection and contemplation in the aftermath of the riots. Several of the clergy stressed that, while finding the words to do so was not easy, they had felt it important to pray for the victims and perpetrators alike, because all are part of the community they serve, and all are loved by God.

There are lessons to learn from these experiences, about the causes of the riots and what preventative measures might be developed going forward. From this, we offer policy recommendations on cohesion and resilience policy, community engagement, youth provision, education, community spaces, mediation and the longevity of funding structures.

The report begins with a quote from Paul Lynch’s Booker Prize–winning novel Prophet Song:

“What is sung by the prophets is but the same song sung across time… that the world is always ending over and over again in one place but not another and that the end of the world is always a local event, it comes to your country and visits your town and knocks on the door of your house and becomes to others but some distant warning, a brief report on the news, an echo of events that has passed into folklore.”

In order to heal, as communities and as a country, from the events of this summer, it is important that they do not too quickly become “but an echo passed into folklore”. If there is one message that came through in every interview with a church leader in this research, it was the hope that we do not rush to find easy solutions but rather engage in the deep listening needed to genuinely restore fractured lives and communities. Our hope is that this report will equip and encourage policymakers and churches alike to begin that process.

You can read the full report here.

Interested in this? Share it on social media.

Join our monthly e–newsletter to keep up to date with our latest research and events. And check out our Supporter Programme to find out how you can help our work.

]]>

Ian Geary examines how the assisted dying bill does not entirely align with traditional Labour Party values. 28/11/2024

Tomorrow, the House of Commons has the Second Reading of the Terminally Ill Adults (End of Life) Bill. The bill has generated much comment, and readers will be well acquainted with the general objections from the bill’s lack of safeguards to bleak evidence from the international context.

Some of that comment – especially last weekend – has been around the role of religious faith in objections to the bill. As a Christian, I entirely support the right of believers to comment on this topic, even with explicitly theological reasons should they so wish. However, as a lifelong Labour supporter, I want to reflect not on the religious arguments but on – so to speak – the other end of the spectrum. I want to argue that the bill does not align entirely comfortably with traditional “secular” or “progressive” Labour values, which some in my party profess to adhere to.

The Labour Party is (putatively) the party of solidarity with the working class, still institutionally true by virtue of its organic link with the trade union movement. It has long been perceived as the party of social justice, with a particular care for the poor and vulnerable. Imperfectly so, certainly, yes but the association exists and this matters.

The potential consequences of this bill risk undermining this association, leading to an adverse impact on citizens from vulnerable backgrounds, in particular the poor, the disabled, and the working–class. Recent evidence from Canada pointed to the impact of the Medical Assistance in Dying (MAiD) legislation in Ontario and the fact that 29% who were ‘euthanized’ for conditions considered ‘non–terminal’ came from poorer areas, and led some to conclude that – in non–terminal cases – poverty is a material factor leading to this outcome. This has nothing to do with compassionately ending someone’s life to end unbearable suffering.

When ‘end of life’ becomes an option, the grim reality is that the poor, disabled, mentally ill and elderly risk being coerced into a decision to end their life – as again, Canada’s MAiD programme of euthanasia has shown. In other words, there is a class component at play.

This approach to the issue invariably draws in the wider discourse around choice. The last time this matter was debated by MPs, ‘choice’ was mentioned 47 times during the debate and Rob Marris MP, the Bill’s sponsor stated that, “there has been a trend in our society, which I support, that if the exercise of a choice does not harm others, in a free society we should allow that choice.” As Nick Spencer observed in an earlier Theos blog, this remains a key argument this time round. “All I’m asking for is that we be given the dignity of choice,” Esther Rantzen has remarked.

On the surface this sounds reasonable. However, the underlying assumptions behind the statements call for scrutiny. What constitutes harm to others? Does choice always drive the good? And who really has choice? The vulnerable and suffering, or the powerful and professional?

It is ironic, to put it mildly, for those on the left to draw heavily on the argument from choice given how ‘choice’ is the register of the free market. (In the light of this, it is also ironic that the bill is being debated on ‘Black Friday’, a new festival of, and stimulus for, consumer choice). The market is encroaching everywhere. Choice – posited as an apparently unalloyed agent of consumerism – requires explanation in its given context.

The choice for some to buy and sell might seem an unalienable right. But the logic of the market does not fit well with the values of the left: solidarity, fellowship, social justice and care irrespective of financial value. We need to consider the necessity of limits to the power of the market so the choices of others, i.e. the powerful, do not impinge on the weaker members of society. In fact, choice is normatively posited as an individual, rather than a collective act. As Bishop Graham Tomlin said is his opinion piece in The Times on 23 November, choice is not the final word on ethical matters, no matter how strong ones convictions might be.

However strong the popular association between legalising assisted dying and progressive politics may be, it is striking how many prominent Labour figures, such as Gordon Brown and Diane Abbott, have come out against the bill. The fact points to there being another way for the left here, a more authentically ‘Labour’ approach to assisted dying, which is to fund high–quality palliative care and grant it the esteem it deserves. Earlier this year, the All–Party Parliamentary Group on Hospice and End of Life Care in their report, ‘Government Funding for Hospices’ called for strategic action stated that, “the UK Government must produce a national plan to ensure the right funding flows to hospices.” Gordon Brown has made a similar call this past weekend. This is surely the way forward at this juncture.

As I noted earlier, many people oppose this bill on religious grounds. They have every right to do so. Christian beliefs underpin my approach also. However, the potential drawback with this approach is that it ends up subtly ‘bifurcating’ views on the issue – anti = the religious, along with some fellow travellers; pro = the secular, the progressive, the Left. This is not the case. It needs to be stated that the case for assisted dying is no more intrinsically progressive than that against it is narrowly religious. As a Christian and a Labour party member, I believe the left should reject an approach based simply on ‘choice’ and see its way to protecting the poor, honouring social justice and in ensuring that our fellow citizens, when faced with their life’s final season, are supported towards a good and compassionate death.

Interested in this? Share it on social media.

Join our monthly e–newsletter to keep up to date with our latest research and events. And check out our Supporter Programme to find out how you can help our work.

]]>

Nick Spencer speaks with Dean and Fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge, Michael Banner. 26/11/2024

The demand for post–colonial nations to pay reparations to, and for their treatment of, their former colonies has grown increasingly loud over recent years. And although many dismiss the idea as textbook liberal guilt and bandwagon wokery, there are some serious claims behind it.

The topic kicks up some big moral issues. You can’t talk about colonial reparations without working through what you think about moral responsibility, collective identity, and the effect of time on liability, all of which reflect on the underlying question of how we see ourselves.

So, what is the nature of our relationship to other countries, to the past and to whatever moral norms we pride ourselves on?

Purchase Michael’s book here.

Interested in this? Share it on social media. Join our monthly e–newsletter to keep up to date with our latest research and events. And check out our Supporter Programme to find out how you can help our work.

]]>

Chine McDonald looks at assisted dying and the underrepresented (and different) perspective of black people. 26/11/2024

Over the past few weeks, I’ve heard arguments from politicians and activists, campaigners, writers and celebrities arguing in favour of assisted dying. I can’t recall many – or indeed any – of them being black. As we approach the vote on assisted dying this week, I’ve been struck by how arguments in favour have held to very white, Western concepts of what it is to be human.

The fact is, we are much less likely to find black people on the ‘pro’ side.

Recent data from the Nuffield Council on Bioethics has borne this out. Their poll found that black respondents are much less likely to support assisted dying legislation: just 43 per cent of black people compared to 75 per cent of white respondents were in favour.

Why might black communities be more hesitant about assisted dying legislation? I can hazard some guesses.

The first is of course that religious views are likely to play a part. Ethnic minorities in the UK are more likely to belong to a religious tradition, where there are strong views about the sanctity of life. Research from the Nuffield Council found that support for assisted dying legislation was stronger among atheists (82%) compared to Christians (66%), Sikhs (52%) and Muslims (30%).

Religious views aside, one thing is glaringly obvious to me: for many Black Britons, our sense of self straddles the divide between our cultures of origin and the Western frameworks in which we exist – the liberal versus the communitarian. Assisted dying is one of those topics in which there is a clash of cultures: a clash between the individualistic culture of 21st century Europe, and the interdependent communities from which we hail.

Many people will be familiar with the southern African term ‘Ubuntu’, which means ‘I am because you are’. In my own community – the Igbo ethnic group of south–eastern Nigeria – there is the concept of the Umunna: the fraternity, the clan or the community. In Igbo tradition, just as in many African communities, there is a strong sense of existing not as an individual , but knitted into a family. One body, with many parts, to allude to the passage in Corinthians.

The idea that someone who is facing death might not want to be a burden, whether due to illness or old age – as some arguments in favour of assisted dying might suggest – is anathema to West African tradition. You can’t be a burden because you are not a separate entity. You’re part of a whole.

We live and we breathe and we create families of our own within the context of the wider, interdependent community. We die within that community too.

Now there are, of course, challenges with this. My generation of British Nigerians will tell you of the frustrations of knowing that what might feel like our business (academic grades, who we marry, where we live, our birth stories) seems to be our whole family’s business – whether that family is here in the UK, or back home.

Polling from More in Common found that women are on average eight points more likely than men to say that, when it comes to assisted dying legislation, safeguards are essential. I would be fascinated to see how that data differed among black women like me, in particular.

Recent years have seen much discussion about health disparities for black women in maternity care, where they are four times more likely to die in childbirth and in the year after giving birth than white women.

The medical profession has not done enough in recent years to allay black women’s fears about giving birth. It would be unsurprising therefore that they might not trust the healthcare system when it comes to assisted dying, either. Can we really trust that – in a stretched NHS, where there are not enough beds, not enough resource to deal with demand – enough has been done to safeguard against racial bias? Can we really be sure that when it comes to someone making a ‘choice’ about whether they live or die, assisted by medical practitioners, that these will be totally free of racial prejudice?

There are those who would argue that such a view is pure hyperbole – that society has moved on from the days of racial discrimination. But tell that to the 65% of black people who have experienced discrimination by healthcare staff because of their ethnicity.

And who can blame black communities for not trusting the system?

We saw during the Covid–19 pandemic how the burden fell disproportionately on ethnic minority communities in the UK, and how some of this was down to lower vaccination uptake among them due to hesitancy about the healthcare system. An article in the British Medical Journal cited institutional racism, historical medical mistreatment of black people and cultural segregation as contributing factors.

If assisted dying legislation passes, then one can only imagine what might happen among some of these communities. You can see how hesitation about seeking medical help might increase, for fear that one will be ‘recommended’ by two medical professionals for euthanasia. Assisted dying proponents might argue that there will be enough safeguards in place to prevent this, but there has not been enough work to allay fears of black communities thus far. We need more time to discuss the wide–ranging implications and the ripple effects into communities like my own.

My colleagues have written on ideas around dignity, vulnerability and being a ‘burden’when it comes to the assisted dying debate.

As Marianne Rozario has written it ‘robs loved ones the time and space to care for relatives that once cared for them… We are denying the time others get to care for us, to love us.’ This is part of the beauty of being from a community whose roots lie in Africa or the Caribbean: the idea of oneness and interdependence is up front and centre in our common life.

I’ve seen this as I’ve witnessed my own family members rallying together, giving their time and money and prayers to relatives in need; how they have opened their homes and searched deep in their pockets for money to pay for relatives’ healthcare, even when things looked at their bleakest. This doesn’t have to be a close relative, but anyone who might be considered part of the clan, part of the Umunna. I have watched and been amazed by how they have nursed each other through the most ‘undignified’ moments.

In my tradition, being burdened by others’ vulnerabilities is part and parcel of what it is to be human. Maybe this is exactly what it means to be family.

Interested in this? Share it on social media. Join our monthly e–newsletter to keep up to date with our latest research and events. And check out our Supporter Programme to find out how you can help our work.

]]>

As the Assisted Dying bill seeks to minimise vulnerability, Marianne Rozario explores the beauty in being cared for and caring for others. 22/11/2024

Being physically vulnerable is not a subject we often want to talk about. It is not comfortable because today’s society teaches us to aim for physical independence, the ability to look after and care for oneself. You don’t want to be, they say, a “burden” on others.

But what if vulnerability is not a flaw to be overcome, but a display of love?

We enter the world vulnerable: a baby in need of support, cared primarily by our parents and those closest to us. And in most cases – as most people die a natural death – we leave this world vulnerable, cared for by those who love us, assisted by medical and social support.

Whilst we must acknowledge that sometimes the “burden” can feel too heavy and vulnerability inadvertently nearly crushes the other, what happens to a society when that vulnerability is denied? Assisted suicide denies our vulnerability, and denies us of a chance to receive and give love.

The current assisted suicide bill being debated in the UK Parliament may appear to have tight regulations, but nonetheless the logic behind assisted suicide is that vulnerability should be avoided. For it proposes that before we are dependent on others for care, we should have the right to choose to end our life. The problem is that, in doing so, we are retreating from a key moment in which, naturally, we feel the practical loving care of others. Being in a state unable to care for oneself, reliant on others for the most basic actions like washing or feeding, should not be viewed as being a “burden” on society, but rather as allowing oneself to be cared for. It is in being vulnerable, we receive love.

At the same time, assisted suicide robs loved ones the time and space to care for relatives that once cared for them. We are denying the time others get to care for us; to love us. Anyone who has nursed a dying person knows that, whilst it may be extremely difficult, it is one of the most beautiful and profound moments of life. Like the prayer by Saint Francis of Assisi goes, “for it is in giving that we receive”; it is in caring for the vulnerable, that we receive.

Those two touchpoints – being in a state of physical vulnerability allowing yourself to be cared for, and being a carer looking after someone who is at their most vulnerable – are when we are closest to knowing love; to touching the face of God, for God is love. This form of love, as agape, is characterised as self–giving, unconditional care for others, and willingness to sacrifice.

Christianity has something powerful to say about vulnerability. From His birth in a humble manger to His crucifixion on a cross, Jesus showed His willingness to be weak, dependent, and vulnerable in the face of human suffering and imperfection. In an ultimate act of vulnerability, Jesus surrendered himself completely, even to death, for the salvation of humanity. In this sense, Christians embrace vulnerability, especially in times of suffering or sacrifice, as imitating Christ’s redemptive love.

Moreover, vulnerability is an essential part of Christian community and the call to love one another. Christian thought teaches that, as members of the Body of Christ, it is necessary to bear one another’s burdens, following the commandment of Jesus to love one another.

Christian understandings of vulnerability challenge us to embrace our own weakness, trust in God’s grace, and offer support to those in need. Vulnerability is, therefore, not a sign of defeat but an invitation to experience deeper intimacy with God and with others.

A society that denies vulnerability – and actively directs us away from it – is a society that has forgotten what it means to be loved and to love.

Interested in this? Share it on social media. Join our monthly e–newsletter to keep up to date with our latest research and events. And check out our Supporter Programme to find out how you can help our work.

]]>

Nick Spencer speaks with Einstein Forum in Germany Director, Susan Neiman. 19/11/2024

Depending on who you are, you might understand “woke” to mean “concerned with fundamental human justice”. Alternatively, you might think its means obsessed with identity politics, tribal, angry, and inclined to cancel and censor.

Either way, you probably associate the term with the left. After all, “lefty” and “liberal” and the words most commonly paired with “woke”.

But what if that isn’t the case? What if it’s an oversimplification? What if woke isn’t left and left isn’t woke? Where does that leave the left? And where does it leave wokery?

Interested in this? Share it on social media. Join our monthly e–newsletter to keep up to date with our latest research and events. And check out our Supporter Programme to find out how you can help our work.

]]>

John Milloy gives us an insight into the realities of legalising assisted dying from Canada. What lessons can the UK learn? 18/11/2024

How did assisted dying become so commonplace in Canada? Like the old quote about bankruptcy, it seemed to happen slowly and then all at once.

In 2016, in response to a Supreme Court decision, the Canadian Parliament passed a law allowing those whose death was “reasonably foreseeable” to seek assisted dying. The law was later broadened in response to another court decision to include those whose death was not imminent but who had a “grievous and irremediable” condition.

That was not the end. The province of Quebec recently allowed advance requests where someone diagnosed with an illness like dementia can agree to be euthanized in the future once they have declined and can no longer give consent. And although the government has promised to extend Medical Assistance in Dying (MAiD) as it is known in Canada, to those with mental illness, they have delayed its implementation until 2027.

Despite being initially presented as a procedure of last resort, the rate of increase in Canadians accessing MAiD is the fastest in the world.

Does the Canadian experience hold any lessons for the UK? I am a retired Canadian politician teaching public ethics at an Ontario university and I would never be bold enough to advise UK citizens about how they should decide this issue. The Canadian experience might, however, help inform your debate.

This is about more than individual freedom

Unlike other emotional debates, such as the one over same–sex marriage, assisted dying never prompted the type of heated discussion in Canada that might have been expected. Many saw it as simply an issue of personal choice. Few seemed to question what type of society we were creating. Was it appropriate to create a system where doctors or nurse practitioners routinely help those desperate to die kill themselves? We also rarely discussed whether assisted dying was the right response to suffering, decline in quality of life, or a perceived loss of dignity.

This was a significant oversight. Studies show that Canadians accessing MAiD seek the procedure for reasons that often go beyond immediate pain, including: the inability to participate fully in daily living or pursue meaningful activity; loss of control of bodily functions; fear of being a burden; or even because of loneliness.

Instead of simply offering assisted dying, did we need to rethink concepts like “meaning” and “dignity”? One of the few groups to raise those questions in Canada were persons with disabilities who continue to challenge assisted dying as a response to physical limitations or fear of being a burden.

Might assisted dying become a response to underfunding in our healthcare and social assistance systems? During the initial debate in Canada, such questions were dismissed as alarmist. But since then, we have seen studies and media stories about individuals accessing the procedure because of poverty or the inability to find medical treatment. Perhaps most concerning, about one third of Canadians surveyed support poverty as a reason to seek assisted dying.

Once the procedure is in place, further discussion is difficult

As someone working in the field of public ethics, I found the original debate over assisted dying different from discussing other controversial issues. While the procedure remained hypothetical, concerns could be freely raised without causing offense. Then the law was passed and the circle of those with a loved one who had accessed MAiD began to grow. An air of defensiveness began to take hold, and assisted dying joined the ranks of those issues that progressive people don’t question.

That point became apparent to me when I witnessed a Member of Parliament correct someone for using the term “assisted suicide”: “We need to call it Medical Assistance in Dying”, she said, “so as not to stigmatize those who access it.” Allowing a narrow law to be passed and taking a “wait and see” approach won’t be doing yourself any favours.

Limiting it to only those who are dying will not end the debate

Canada’s original decision to limit MAiD to those whose death was “reasonably foreseeable” didn’t end the debate. Why only those at the end of their life? What about those who live daily with intolerable suffering with no relief in sight? What about individuals with severe mental health issues? Shouldn’t those diagnosed with dementia be allowed advance consent to access the procedure in the future?

It was difficult to respond as we hadn’t worked through why MAiD was only limited to the dying. As Nick Spencer pointed out in a recent Theos blog post, “unless there is an underpinning philosophical logic” behind who can and can’t access assisted dying, it is difficult to argue against its expansion.

When a lower court ruled that the law must be broadened, the Canadian government didn’t appeal the decision even though many experts felt there were legal grounds. Because we hadn’t firmly established why only the dying were eligible, there was a sense that the law’s expansion was inevitable.

Where will it end? The Canadian government is considering offering advance requests nationwide. Will the procedure be extended to those with mental illness in 2027? Many Canadians oppose the idea including the opposition Conservatives who are ahead in the polls, but the absence of clear reasoning as to why any category of suffering should be excluded has made debate difficult.

Conclusion

There is considerable support for MAiD in Canada. It has, however, changed us as a nation and not necessarily for the better. I often ask myself whether it has weakened our collective sense of responsibility to support and encourage those who feel their lives have lost meaning. The speed with which we made assisted dying part of our culture has me feel more than a modicum of remorse. I hope that the people of the UK consider all the implications before moving forward.

Interested in this? Share it on social media. Join our monthly e–newsletter to keep up to date with our latest research and events. And check out our Supporter Programme to find out how you can help our work.

]]>

The feeling of being a burden fuels the assisted dying debate. Nick Spencer reminds us that caring for each other is part of being human. 14/11/2024

Kim Leadbeater’s long–awaited assisted dying bill has been published. The conversation can now start in earnest.

That conversation will, quite rightly, encompass multiple details… the funding available for palliative care, the medical accuracy of relevant diagnoses, the legal and regulatory frameworks in Canada, Oregon, and elsewhere. Many of these are explored in a new book – talk about good timing! – published by Open University Press on The Reality of Assisted Dying, and edited by Ilora Finlay and Julian Hughes, to whom I spoke for this week’s episode of Reading Our Times.

Underlying many of these details, however, is the question of how we understand ourselves. This question also has many different perspectives or dimensions to it. What is a human being worth? How far should our autonomy extend? What is the nature of our responsibility to one another? Wherein resides the dignity to which we are all committed? These are the anthropological foundations on which our ethical towers are constructed, upon which we hang our legislative programmes. What we say about ourselves ultimately informs where we go as a society.

One of the things we say about ourselves, and particularly in this debate, is that we don’t want to be a burden on our loved ones. The line is repeated constantly and plays a role even in jurisdictions like Oregon, which have managed to avoid sliding down the slippery slope with the speed and eagerness of Canada. A 2016 report found that almost 50% of patients in Oregon whose lives were ended under the Oregon Death with Dignity Act cited “being a burden” as one of their concerns. (Finlay and Hughes: 17)

“Burden” is a dangerous word, one that morally colours just as much as it describes. The word literally means “a heavy load” but is only really used to describe the kind of load that is too heavy or, at least, the kind of load we would be better off without. No–one says, “she’s just such a burden to us” and means something positive or enviable from it. In this way, introducing the word “burden” into our conversation about assisted dying does the thinking for us. If you accept that we shouldn’t be a burden to our loved ones, job done.

But we shouldn’t accept it, because we are a burden to those around us, and we should be. More precisely, the closer your ties to another human being, the greater the chance that that person will be a burden to you at some point in your relationship, just as you will to them. That’s not wrong. It’s part of being human.

Colleagues are on the periphery. If you do have a colleague who is consistently slope–shouldered, sooner or later they run out of road. But even in the working environment (or, at least, the happy, well–functioning working environment) there are times in which you will carry others’ loads, working late, say, to help them with a deadline or to cover for them as they deal with a personal problem. That burden–bearing is not a permanent feature of the workplace and is usually expected to be reciprocal rather than simply altruistic, but it is there, nonetheless.

Friends are closer. Superficially, they are the fun part of life. Holiday, pubs, parties, dinner tables: that’s where friends belong. But close friends, as opposed to acquaintances, go beyond that, and there are times when you need them, and they need you. That need can be a burden, demanding time, energy, or money that you might otherwise not choose to offer. But offer it you do, for no more reason than they are your friend.

And then there is family… well, does it need to be said? The exhausted, bleary eyes of sleep–deprived new parents… the forced smile and raw–handed applause as mum and dad sit through the third nativity play in a week … the emotional bruising they endure during adolescence… the late–night counsel we offer to siblings… the visits to elderly or lonely relatives… it goes on. These are burdens, heavy loads. And we bear them. We bear them because that is how we would like to be treated. We bear them because we feel it is simply the right thing to do. We bear them because we sense this is what makes us more deeply human. We bear them because they are signs of love and without love we are nothing. “Carry each other’s burdens, and in this way you will fulfil the law of Christ.”

Let’s not get too misty eyed here. Sometimes the burden becomes unbearable, so heavy that it will crush us. Martyrdom is no triumph here, if only because if we collapse under the weight of the burden, the person we are trying to help collapses with us. There are times in life when we cannot cope with what we are being called to carry, and we need others to carry with it us. First family, then friends, neighbours, associations, communities, and ultimately the state (though the modern world has not always preserved that order): we need these institutions to help us with those unbearable burdens.

But that does not change the fundamental picture that humans are here to “bear one another’s burdens”. We are born to carry one another. “If anyone forces you to go one mile, go with them two miles.” We are natural beasts of burden. If we pretend otherwise, if we think the burden is a distraction from who we are – rather than an example of who we are – we will become less than who we are.

Interested in this? Share it on social media. Join our monthly e–newsletter to keep up to date with our latest research and events. And check out our Supporter Programme to find out how you can help our work.

]]>

In collaboration with the Larger Us podcast, Elizabeth Oldfield speaks with musician and activist Daryl Davis. 13/11/2024

Daryl Davis shares a unique perspective on the motivations behind white supremacy and what it takes to see the gradual transformation of KKK members.

Hosts Elizabeth Oldfield and Alex Evans, delve into the extraordinary story of Daryl Davis, a Blues musician who has spent decades befriending and dialoguing with members of the Ku Klux Klan. Driven by a deep curiosity to understand the roots of racism, Daryl has taken an unconventional approach, choosing empathy and open communication over confrontation.

Discover the profound impact one person can have in bridging the divide and fostering greater understanding between communities.

If you enjoy episodes of The Sacred don’t forget to hit subscribe to be notified whenever we release an episode!

Interested in this? Share it on social media. Join our monthly e–newsletter to keep up to date with our latest research and events. And check out our Supporter Programme to find out how you can help our work.

]]>

Nick Spencer speaks with Crossbench Peer and honorary professor of palliative medicine at Cardiff University, Ilora Finlay, and former professor of philosophy and old age psychiatry, Julian Hughes. 12/11/2024

Assisted Dying is back on the legislative agenda, with parliament voting on it this autumn. It is a profound and contentious debate about which good and well–meaning people can and do disagree deeply.

What is really at stake here? Apart from the obvious, the debate kicks up some profound and difficult questions about most important ideas concerning human life.

For example, how far should we respect people’s autonomy and choice? What constitutes a meaningful life? And what is the meaning of human dignity?

Buy a copy of Ilora and Julian’s book ‘The Reality of Assisted Dying’ here.

Interested in this? Share it on social media. Join our monthly e–newsletter to keep up to date with our latest research and events. And check out our Supporter Programme to find out how you can help our work.

]]>

Following the 2024 US Election, Paul Bickley examines how American politics is turning into an existential battle between good and evil. 07/11/2024

Way back on 11 February the Kansas City Chiefs and San Francisco 49ers met at Allegiant Stadium in Las Vegas for the 2024 Super Bowl. For those not in the know, the Kansas City Chiefs claimed victory in a dramatic overtime finish when Patrick Mahomes connected with wide receiver Mecole Hardman for the decisive touchdown. They won 25–22, and so secured their second consecutive Super Bowl win. The halftime show contained all the usual glitz, showbiz and commercialism. TV coverage ran an allegedly funny Dunkin’ Donuts advert starring Jennifer Lopez and Ben Affleck. (Sadly, the joke didn’t last – the couple separated and filed for divorce in April.)

Nine months later and the world is digesting the results of the US presidential (and other!) elections. This every–four–year event is like a political version of the Super Bowl. Large crowds, lots of money, and celebrities – often the same celebrities – endorsing the ‘product’ of this or that campaign. Two teams facing off on the biggest stage imaginable. No prizes for second place.

American politics increasingly looks like a piling up on a series of binaries. It’s not just Republican vs Democrat, left vs Right. It’s urban vs rural; coasts versus flyover; pro–life vs pro–choice; and, in this election, men vs women. For the winning team – elation, power, and the opportunity to shape America and the world. For the other, a billion–dollar failure. Losers.

Of course, religion plays a part in American democracy. By now we are familiar with the ways groups tend to break: white evangelicals for the Republicans (according to the exit polls of the Washington Post, making up around 1 in 5 votes and breaking 81% for Trump). All other religious groups, taken together, lean Democrat, with Harris securing 58% of their votes. In this constitutionally secular democracy, both sides are still ‘going to church’.

But there is something deeper at work, which should also be called religious. A Manichaean spirit has taken hold of American politics, perhaps also American society at large. This is not any anachronistic claim of the revival of the long dead religion of the prophet Mani, but it is something the resembles it. Manichaeism, a kind of mashup of Christianity, Zoroastrianism, and Buddhism that emerged in 3rd century Persia, taught that existence was a struggle between two equal and opposite forces of good and evil, light and darkness. Through ascetic practices of prayer, fasting, and confession the ‘elect’ could help release the light from its imprisonment in matter, which Manichaeans considered inherently evil.

Not that different from Christianity, you might think. Indeed, Manichaeism was, for a time, an influential Christian–adjacent sect in the Roman Empire. But the church and its theologians more and more critiqued and distanced themselves from it. Finally, the Roman Empire suppressed it (as did the Sassanian Empire, where Mani is thought to have died in prison). Famously, Augustine of Hippo was a Manichaean until his conversion at the age of 31. He too became an ardent critic of his former religion.

All this seems like a very long way from Washington DC, but I’ve been reminded of the Manichaeans as political discourse has begun to co–mingle with contemporary ‘conspirituality’, and as many of us have felt the temptation to cast politics as an existential battle between good and evil. We are too apt to see campaigns and elections as the purgative process whereby light will be released from the enmeshing darkness. As anyone watching will have realized, both camps in this election have indulged in this. If you were to believe the utterances of the opposing campaigns , this was a Super Bowl runoff between the Communists and the Nazis – two words which in America are equal and opposite evils, depending who you’re talking to.

Why? Partly because with less social mixing, and more social media echo chambers, it is easier to believe that your political opponents are not only wrong but stupid, and not only stupid but evil. Partly its tactical, yet another way to whip up the base or get the vote out. Ultimately, however, it is partly because both sides believe it. Last Sunday, Kamala Harris spoke at a church in Detroit, Michigan:

We face a real question: what kind of country do we want to live in? What kind of country do we want for our children and our grandchildren? A country of chaos fear and hate or a country of freedom justice and compassion?… Let us turn the page and write the next chapter of our history. A chapter grounded in a divine plan big enough to encompass all of our dreams. A divine plan strong enough to heal division. A divine plan bold enough to embrace possibility: God’s plan.

I admire Harris’ effort to appeal to religious voters in a language that would make sense to them. Churlish though it may be, I can’t help but notice the weaknesses of the implicit theology of statements like this. I would be surprised if God’s plan did = Democratic Party platform, just as I would if it was the Republican Party platform. If it did, then God’s plan is now in tatters, and his purposes junked by swing voters in Pennsylvania and Michigan.

One of Augustine’s complaints about this belief system was that God for the Manichaeans was not God at all. He was limited by matter and darkness. Somehow, it is God and goodness and light that needed to be saved. He also disliked the way Manicheans gave equal ontological weight to evil. For Christians, even those that do find themselves at a bleak moment in history, we are not in an existential Super Bowl contest between good and evil. The powers, said St Paul, have been disarmed and defeated. Christians cannot be Manichaeans.

The pathology in American politics is not the evil of either side, but the tendency of both sides to elevate their politics to the level of cosmic struggle. They overestimate the transformative potential, or wisdom, of their own victories. They will see their defeats as moral failures. The worst are full of passionate intensity, as Yeats wrote. But the best must avoid this Manichaean heresy and hold out for the complicated middle ground of democracy as a means to work slowly, often indirectly, towards the common good.

Interested in this? Share it on social media. Join our monthly e–newsletter to keep up to date with our latest research and events. And check out our Supporter Programme to find out how you can help our work.

]]>

Elizabeth Oldfield speaks with writer and columnist Sarah Ditum. 06/11/2024

Sarah Ditum delves into her journey through the strands of feminism, the misogynistic “upskirt decade”, the invasive celebrity culture of the late 90s and 2000s that often exploited and shamed young women, and her views on the role of pornography and its impact on mainstream culture.

Sarah is a critic and columnist for The Times and The Sunday Times, and author of the book “Toxic: Women and the Noughties.”

This wide–ranging conversation provides a nuanced look at the evolution of feminist thought, the power of media narratives, and the personal experiences that have informed Sarah Ditum’s worldview.

If you enjoy episodes of The Sacred don’t forget to hit subscribe to be notified whenever we release an episode.

Interested in this? Share it on social media. Join our monthly e–newsletter to keep up to date with our latest research and events. And check out our Supporter Programme to find out how you can help our work.

]]>

Nick Spencer speaks with Professor emeritus at McGill University, Charles Taylor. 05/11/2024

For many people, many of whom would not call themselves religious or even spiritual, poetry is somehow able to enchant, to inspire, to heal– to give them a glimpse of connection, of transcendence that transforms their life.

Particularly today, in “A secular age” in the West, it is poetry and indeed the arts more widely that often boast the greatest ability convey that sense of connection and transcendence that seems so important and hard–wired in humans.

What is going on here? How does it work? And what does it say about us as human beings?

Buy a copy of Charles Taylor’s book ‘How the World Made the West’ here.

Interested in this? Share it on social media. Join our monthly e–newsletter to keep up to date with our latest research and events. And check out our Supporter Programme to find out how you can help our work.

]]>

Nick Spencer critiques the idea that ‘dignity of choice’ is the most compelling moral argument in the assisted dying debate. 01/11/2024

Esther Rantzen put it best. Not long after Kim Leadbeater announced her private members’ bill, the former TV star was interviewed by Amol Rajan on BBC Radio 4’s Today programme.

“All I’m asking for is that we be given the dignity of choice,” she said, using a telling phrase that I have italicised here. “If I decide my own life is not worth living, please may I ask for help to die. It’s a choice.” She continued, “I don’t want to pressure anyone either way…it’s the most personal choice…like whether or not to have a baby… I’m asking for choice.”

This is a very widespread sentiment. I have had two conversations in the last week alone with people who were indignant, bordering on furious, that I was prepared to argue against the right to choose the manner of death, especially when it came to someone suffering from a painful and incurable illness.

As noted in a previous blog, I do waver a bit on this issue but, ironically, it is when I hear Esther Rantzen’s words, or words like them, that I am nudged most decisively away from supporting any change in the law.

On the surface, the argument sounds reasonable, indeed obvious. We have been well trained by decades of consumerism to hear ‘choice’ as not only as axiomatic but as morally momentous. If my sentence begins ‘I choose’, you are going to need a damn good reason to deny me. Moreover, the phrase familiar from the abortion debate – “my body, my choice” – so often repeated, so rarely interrogated, so automatically assumed unanswerable, has softened us up for the assisted dying one. “My life, my choice.”

A little reflection shows that “my body my choice” is not really a moral argument at all, let alone an inherently persuasive one. “My body my choice” – really? Does that apply to sex selective abortion? To self–harm? To suicide? So it is with the argument from choice in this debate concerning the other end of life.

Look at Esther Rantzen’s words again. “If I decide my own life is not worth living, please may I ask for help to die. It’s a choice.” Seriously? If you are like me, there will have been a few times in your life that you have felt – deeply felt – that your life is not worth living. I know I am, by nature, a melancholic soul but I doubt whether I am that exceptional in this. I can only thank God that I wasn’t living in Canada at the time where MAiD (Medical Assistance in Dying) is now the fifth commonest cause of death.

Ah! respond those in favour of the Leadbeater bill. That may be so. But that is not what is on offer in this bill. On the contrary, the Leadbeater regulations are highly restrictive, and will remain so.

But they will not remain so, because they cannot remain so. If we really do intend to prioritize ‘autonomy’ in the way that advocates of assisted dying do – if we do want to give people like Esther Rantzen the “dignity of choice” – we no longer have any grounds to deny it to people who argue – with great reason, cogency and unassailable self–knowledge – that they have come to the conclusion that their life is not worth living, and do not want to go on living, and that they want the dignity of choice too. If you put all your eggs in that philosophical basket, you have no tools left to argue against that view (and if you come across a more mixed metaphor today, you should treasure it).

Or, put another way, law is not positivist. It cannot exist solely on the basis of judicial decisions. It needs moral and philosophical ground beneath it. It is all well and good to propose tight restrictions for any incoming legislation, but unless there is an underpinning philosophical logic to them, they will not hold. You will find yourself on a tilting slope – with only the slightest of gradients, perhaps, but tilting nonetheless – without a brake to reach for.

It is no accident that Leadbeater’s bill has already been criticised by some for being too tight. It is no accident that restrictions have been gradually loosened in Belgium and the Netherlands. It is no accident that Quebec has just this week become the first province in Canada to allow people to make advance requests for medical assistance in dying (MAiD), meaning that “a person with an illness that will eventually leave them unable to grant consent can arrange to receive a medically assisted death when their condition worsens, be it months or years in the future.”

It is no accident because there is a perfectly consistent, cogent and coherent logic here. If we think dignity means choice, this is where we must end up. However alluring it may sound, however it is dressed up as compassion, and however much it is the de facto basis of a consumerist society like our own, the fact is that choice is not enough.

Theos’ new report, ’The Meaning of Dignity: what’s beneath the assisted dying debate’ can be read here.

Interested in this? Share it on social media. Join our monthly e–newsletter to keep up to date with our latest research and events. And check out our Supporter Programme to find out how you can help our work.

]]>

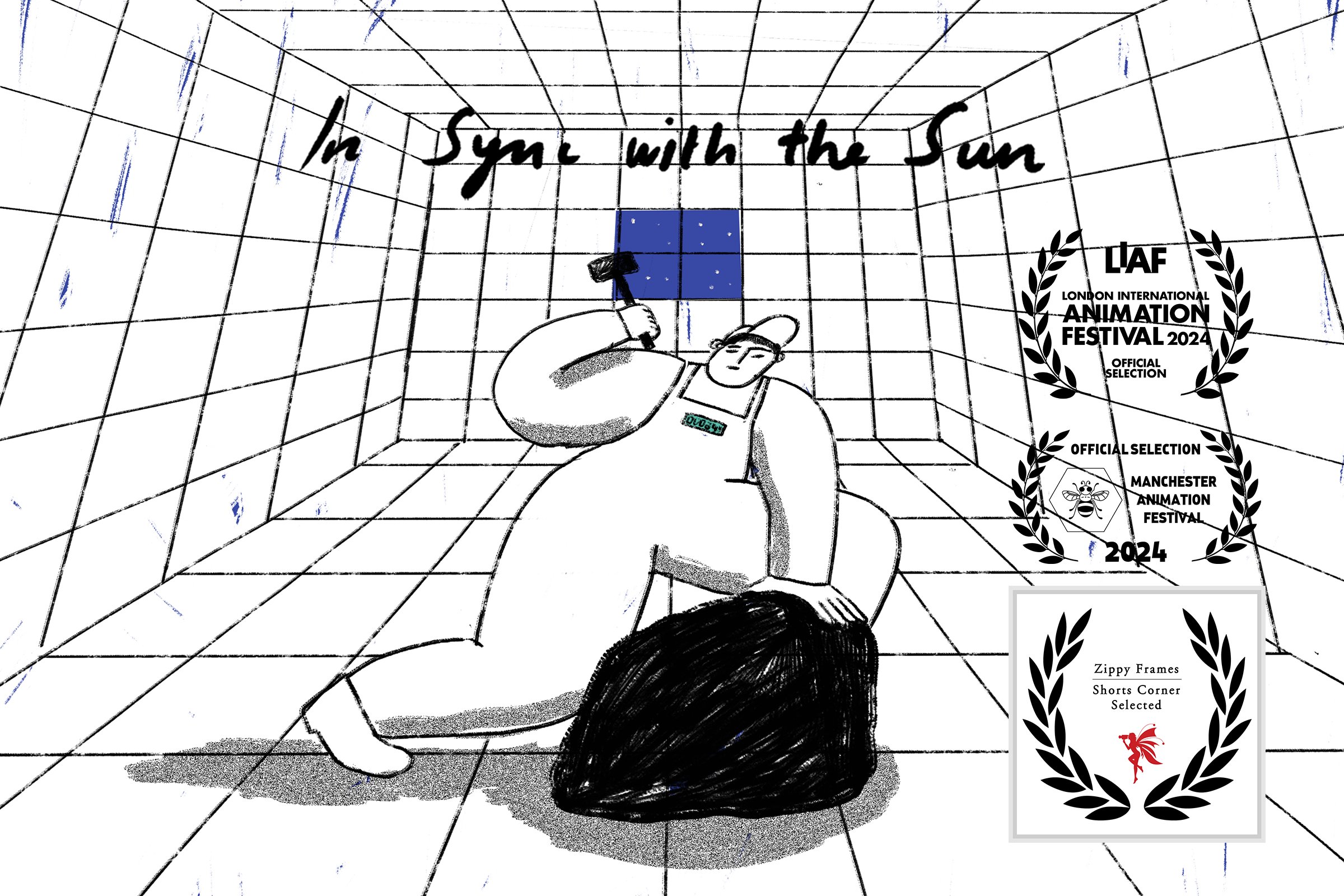

A new animation by Emily Downe exploring what happens when we disturb life’s natural rhythms. How do we understand our worth in a culture that idolises productivity. 30/10/2024

This short film explores the rhythms of waking and resting embedded in the natural world. The film explores the impact of productivity boosting artificial technologies on our world. We can do more, make more, profit more, but without boundaries. But what do we lose when we pursue limitless productivity?

Interested? This animation is part of wider research by Theos on productivity. For more, click here

Script for In Sync with the Sun

The war against sleep began when artificial light broke into the night. It’s an absurdity, a bad habit. ‘There is really no reason why men should go to bed at all’, Thomas Edison said. Be productive. Rest is for the dead.

Slack jawed, drifting into enchantment and mystery,

The unlimited mind

Playtime

A waste of time. Every living thing thrives in cycles of activity and rest,

In Sync with the sun.

Light, dark, sleep, wake, rest, work, play. But for us, artificial light took over the night.

Out of sync.

Marching to the beat of a different drum. Now we decide when the day is done. It never is. Prove your worth. Every second counts. Rest less, burn out. Shut down. Artificial light wasn’t enough. Enter: artificial minds. Limitless machines, relentlessly efficient, A constant bloodless pulse. In the race for productivity, artificial minds may easily win. But what is lost? Creating, caring, giving

Computes productivity: 0. But to us, we see true value. You’re not a machine. Light, dark, sleep, wake, rest, work, play,

Repaint the boundary line,

Make yourself at home. The only thing that can stay awake is not awake at all.

About the Productivity Project

“Productivity isn’t everything, but in the long run, it is almost everything” claimed the economist Paul Krugman. Throughout the twentieth century, productivity improved dramatically across the developed world in a greater increase than in the previous 2000 years. Driven by life changing technologies, such as electricity, combustion engines, and phones, living standards increased sevenfold. But since the 2008 financial crisis, despite computerisation and the internet, productivity growth in many countries has been low, static or even, in the case of Japan, falling.

Is faltering productivity growth a policy problem to be fixed, or is our obsession with productivity (both economic and cultural) an unhelpful measure of true human flourishing?

In this stream of work, Theos explores the changing pressures on (and demands of) our society to argue that we must balance productivity against other measures of success, especially in an increasingly service–based economy and an age of climate crisis. We particularly explore the natural limits of human attention and the planet we call home, as well as the likely impacts of artificial intelligence, to ask: what does a productive human really look like?

Film Credits

Written, directed and designed by Emily Downe

Animated by Emily Downe and Martha Halliday

Music and sound by Jan Willem de With

Additional sounds by Richard Johnsen

Produced by Theos with thanks to The Fetzer institute

Interested in this? Share it on social media. Join our monthly e–newsletter to keep up to date with our latest research and events. And check out our Supporter Programme to find out how you can help our work.

]]>

Elizabeth Oldfield speaks with writer and editor Rod Dreher. 30/10/2024

Rod Dreher and Elizabeth Oldfield delve into Rod’s journalism of the Catholic sex abuse scandal, converting to Eastern Orthodoxy, his views on immigration and Donald Trump and supernatural experiences.

Chapters

00:00 What is Sacred to you? Rod Dreher answers

06:28 Family, Place, and the Weight of Expectations

10:16 Moral Foundations and Personal Crisis

17:54 The Benedict Option: A Call to Intentional Living

26:25 The Journey to Orthodoxy and the Search for Transcendence

30:39 Living in Wonder: Rediscovering the Enchanted World

33:03 The Unseen Battle: Spiritual Awareness

36:44 Encounters with the Divine: Transformative Stories

39:41 Spiritual climate

43:03 Conservative politics, Trump and faith

48:42 The willingness to suffer for your beliefs

Interested in this? Share it on social media. Join our monthly e–newsletter to keep up to date with our latest research and events. And check out our Supporter Programme to find out how you can help our work.

]]>

Nick Spencer speaks with Professor of Ancient History, Josephine Quinn. 29/10/2024

About 30 years ago, the American political philosopher Samuel Huntington wrote a hugely influential book entitled The clash of civilizations in which he predicted that the ideological wars of the 20th century would give way to civilisational ones in the 21st.

The book drew criticism for the way it talked about “civilizations” as if they were hard edged and obviously identifiable things. Because the general idea of civilizations is a relatively recent one, and if we peer into the mists of time, we can make out the many streams and tributaries that have poured into the West over the centuries to make it what it is.

So, where exactly is our civilisation, “the West”? How has it been shaped by “other” cultures? And what does that mean for us today?

Buy a copy of Josephine Quinn’s book ‘How the World Made the West’ here.

Interested in this? Share it on social media. Join our monthly e–newsletter to keep up to date with our latest research and events. And check out our Supporter Programme to find out how you can help our work.

]]>

Nick Spencer on the role of emotive stories in the assisted dying debate, and what role they should play. 24/10/2024

“I have to confess to you I’m finding the conversation a distressing one because of [its] tendency to look away from the situation and to deny the reality.”

So spoke Kit Malthouse MP during a discussion about assisted dying debate, run by the Religion Media Centre last week, in which I participated.

He was responding to points that I and others had made about some of the more theoretical issues underlying the debate: dignity, choice, social responsibility, religious duty, and the like.

His point, made with a little frustration but no rudeness, was that discussion about these matters is all well and good but fails to face the grim reality of people dying in despair and pain. “People are already killing themselves”, he explained. “Several hundred a year are blowing their brains out, taking overdoses… deciding to refuse treatment and starving themselves to death because they’re in such pain and agony.” The “willingness to look away from the horror story of the situation,” he concluded, “is quite distressing.”

A subsequent speaker did pick him up on this. Given that people who campaign against assisted dying usually support – indeed base many of their arguments on – palliative care, they can hardly be accused of looking away at the moment of people’s suffering.

But Malthouse’s comment did, albeit inadvertently, highlight one very important dimension of the assisted dying debate that merits attention.

Those arguing for assisted dying have many upsetting stories on which they can draw. Estimates of the number of people receiving palliative care but who still die in pain range vary. One study from 2019 calculated that of those who die in a hospice, an average of 13.4% experience some level of unrelieved pain (1.4% not at all relieved, and 12% only partially relieved). It’s an uncomfortable fact for those who argue against assisted dying and is made all the more so by the often tragic, and sometimes lurid, stories of people dying in despair, as well as pain, at the end of the life. I am, on balance, against legalising assisted dying (for reasons to be explored in later posts and in the forthcoming Theos report, The Meaning of Dignity). However, after having listened to such stories, I seriously teeter on the brink of changing my mind. Do I really want to be one of those people responsible for others dying in this way?

The problem with reaching the decision this way, however – dragged over to one side by the power of heart strings tugged – is that different stories, equally tragic, equally lurid, can easily drag you back to the other.

Take the story of the 71–year–old man from Canada who was told he was terminally ill with end–stage Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD), offered Medical Assistance in Dying (MAiD), and euthanized within 48 hours of his first assessment but who, it was discovered on autopsy, did not in fact have COPD. Or the story of the 29–year–old Dutch woman who was granted euthanasia on the grounds of unbearable mental suffering, despite being in good physical health. Or the story of the Canadian man in his 40s with inflammatory bowel disease, socially isolated and addicted to opioids and alcohol, who was told about MAiD during a psychiatric assessment and driven to the location where he received an assisted death, without his family being consulted. If one set of awful stories pull you on to one side, another set will pull you back.

There are responses to such stories. For example, those in favour of assisted dying will say, yes, there are tragic and upsetting stories, but we can build in safeguards against such slippage. We don’t have to end up like Canada.

On the other side, those against it will say, yes, there are tragic and upsetting stories, but palliative medicine is good despite being chronically underfunded. Just think what palliative care might achieve if only we, as a society, decided seriously to invest in it. That was more or less the substance of Health Secretary Wes Streeting’s recent intervention against the bill.

And then there are responses to these responses. You probably already know them. More to the point, you can probably already guess the point I’m trying to make herе.

Tragic, upsetting stories are relevant to this discussion. They are part of the ‘legitimate evidence base’, if that isn’t too cold a term. We should not, we cannot, “look away from the horror story of the situation” as Kit Malthouse rightly said.

But nor should we allow such stories to make up our minds, as he was implying. Just as we cannot ignore the practical “evidence” – whether that is people dying in despair or being euthanised for being depressed or (not actually) ill – nor can we ignore the principles through which such evidence is interpreted. Questions of dignity, autonomy, responsibility and the like may seem, to some, unnecessarily abstract, but they are an essential part of the debate.

All this may seem obvious, but I fear it needs saying. It is precisely because personal tragedy makes such good journalistic copy, that there is a real and present danger that the debate will be decided by those who can tug at the heart strings most successfully. That, in itself, would be a tragedy. We owe it to ourselves to think about this issue, as well as just to feel it.

Interested in this? Share it on social media. Join our monthly e–newsletter to keep up to date with our latest research and events. And check out our Supporter Programme to find out how you can help our work.

]]>

Elizabeth Oldfield speaks with writer and Catholic priest, Fr James Martin. 23/10/2024

Father James Martin and our host, Elizabeth Oldfield discuss his journey to becoming a Catholic priest and the Jesuit motto of finding God in everything. We spoke about the difficulty of living a life of chastity, becoming a vocal advocate for LGBTQ inclusion within the Catholic Church and navigating backlash as a public figure.

Purchase Fr James Martin’s new book ‘Come Forth’ here: https://www.eden.co.uk/christian-book…

Chapters

00:00 What is Sacred to you? Father James Martin replies

00:54 Understanding the Sacred

02:50 The Role of Discernment in Life

05:46 Childhood Influences and Early Life

09:08 Transitioning from Business to Jesuit Life

11:56 Exploring Religious Orders

14:51 Community Living and Its Challenges

18:10 Chastity is difficult

20:05 Having a public voice

23:00 Advocacy for the LGBTQ Community

27:16 Spiritual Rejection and backlash

32:06 Understanding Radicalisation and Disagreement

34:32 The Role of Politics in Division

38:58 Finding the Balance in Discourse

40:24 Exploring the Themes of ‘Come Forth’

44:44 Jesuit Wisdom on Understanding Others

49:06 The Importance of Connection in Disagreement

The Sacred with James Martin

What is sacred to you? Father James Martin responds.

Elizabeth

Father James, we’re going to kick off with a question that you can really take in any direction you like. For people who aren’t coming from a religious perspective, it’s often more about their deep values and principles. I’m trying to get a sense of what you would like to be orientating you in your life. So I’m going to ask, what is sacred to you?

Fr James Martin

Oh gosh. Well, first of all, thanks for having me on, it’s a real honour. What is sacred to me? You know, I’m a Jesuit, and one of our mottos is finding God in all things. And so I guess I could say everything really is sacred. That doesn’t mean every act is sacred, but you know, every person you meet is sacred. I think everything that’s created by God is sacred. But you know, in my life, the sacred is really focused around Jesus, that’s what the heart of my spiritual life is about. So I would say, in my life, it’s not so much what is sacred, but who is sacred? And that would be, for me, Jesus.

Understanding the Sacred

Elizabeth

For someone who that’s not their tradition. Honestly, the question that comes up is, what does that mean? What does it look like for you?

Fr James Martin

I know, it is kind of crazy. So what does that mean? There’s two ways of answering that question. So as I said, I’m a Jesuit, and one of our mottos is finding God in all things. And that means that God can be found not just in reading the Bible or doing good works or going to church or praying, but in relationships and family and work and nature and art, which is really a very capacious spirituality. That that’s the first thing that I mean when I talk about the sacred. But the center of my faith is really focused on Jesus. Now, what does that mean? You’re right, that can be vague. So it means Jesus as we meet Jesus in the gospels, you know Jesus’ actions, his words and his deeds. But we also believe that Jesus has risen from the dead and is present to us through the Holy Spirit, and so through the Spirit, is sort of leading us to do good things. We find Jesus in the church and in the sacraments. So there’s all sorts of ways of encountering Jesus. So yeah, I would say that when I hear ‘sacred’, those are the two things that come up: finding God in all things, the sacred in everyday life, and also the person of Jesus. That that’s how I would answer that question for me, at least.

The Role of Discernment in Life

Elizabeth

Can you think of a moment in your life when those sacred things have been tested. I often think we’re not sure what are the things we’re trying to live by sometimes, until these moments of challenge or moral profundity or the temptation to compromise. You know, when we’re at a fork in the road and our life could go one way or the other, can you think of a moment where they have guided you, and sometimes we fail so you might not have chosen what you would have wished to at the time, but does anything come to mind?

Fr James Martin

I mean, I think just things recently, you know, in my own life. One of the things that’s helpful to understand is that we Jesuits talk about, this is going to sound like a very strange term, discernment of spirits, which sounds like it’s like ghosts flying around! But it basically means that there are impulses, movements, when I say voices, I don’t mean actually hearing voices, but you know the movements within you, voices that pull you one way or another. And there are impulses and movements and voices that pull us towards God, right? The charitable, loving, hopeful impulses and wants to move us away from God, selfish, mean spirited, despairing. And what we talk about in the Jesuits is, not only that God wants us to make good decisions, but God helps us to make good decisions through what we call discernment of spirits. In other words, you can kind of gage within yourself, what’s coming from God and what’s not coming from God. And recently, I was in a situation I want to get too detailed, where I just felt really despairing and just kind of miserable and turned in on myself. And I, thanks to discernment of spirits, said, this is clearly not coming from God.